Innocastle Climate Change Webinar

On 17 November 2021, we co-hosted a webinar called “Building Resilience: Monitoring and adapting historic estates to climate change risk” as part of our Interreg Europe project, Innocastle.

At INTO, we are committed to promoting the work of our members in climate action. We were delighted to showcase some of their work in climate mitigation, adaptation and communication at COP 26 in Glasgow last month.

The consequences and scale of climate change are daunting. Historic landscapes of all types are under pressure from both hotter drier weather and more floods and storms. And extreme weather like this, changes in temperature and future water availability will begin to alter the character of parks and gardens, whose particular species are part of their appeal. It seeks to exchange experiences in monitoring the impacts of climate change on historic castles, manors and estates – and to share strategies for adapting to these risks. In this, we can learn a lot from each other.

This webinar has been organised by the Province of Gelderland (Paul Thissen), Gelders Genootschap (Elyze StormsSmeets) and the International National Trust Organisation (Catherine Leonard) in collaboration with all the Innocastle partners. Fifty participants from all over Europe and even further abroad attended the webinar.

Introduction

The workshop began with a welcome and introduction by the chair Dr Elyze Storms-Smeets, on behalf of Team Gelderland. Elyze spoke about climate change as one of the biggest issues we face today, citing the flooding of towns in the Netherlands and Germany only last summer. But it’s not only extreme flooding that puts our heritage at risk. It’s also extreme drought, sometimes even at the same place. How can we cope with these extremes? Might understanding how the historic landscapes were used and developed in the past help solve the issues we are facing today?

Monitoring climate impacts

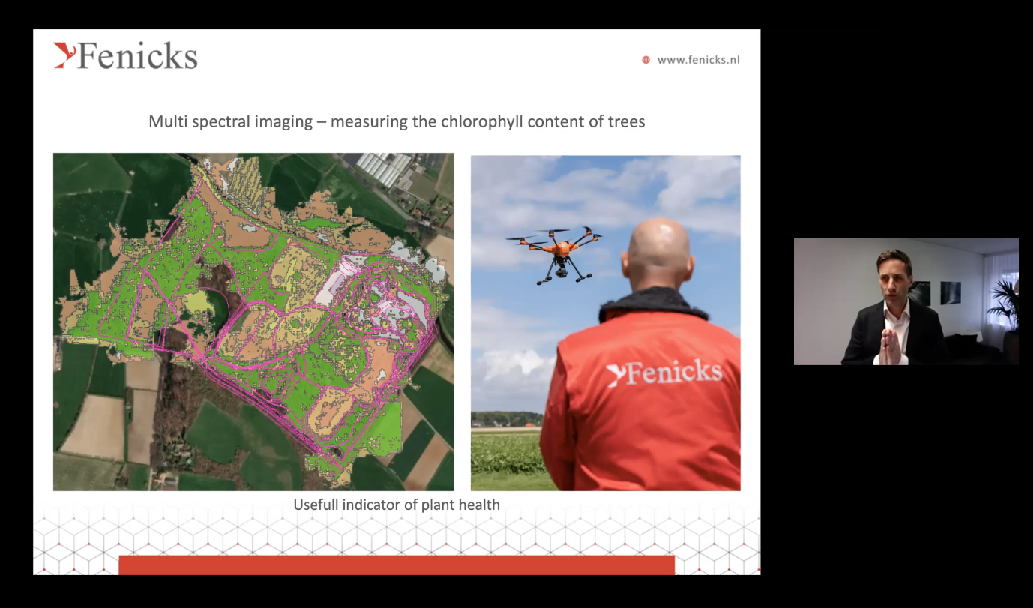

Jennemie Stoelhorst of SKBL, and Jan-Hylke de Jong from Fenicks then introduced tools for monitoring the impacts of climate change on Dutch country houses and landed estates. The aim of which is to map the consequences of climate change for green and blue heritage on country estates and estates, to collect and share knowledge about and experience with possible measures.

And technology is helping. For example, we learned about a drone with a multi spectral camera that flies over the estate to measure the chlorophyll content of each tree in order to assess their health level. The images produced by the drones can also help to locate dead trees or trees that were damaged by storms for example. Soil moisture is measured using a satellite. And this analysis can be done daily so it gives real time data of the different cycles an estate goes through in a year.

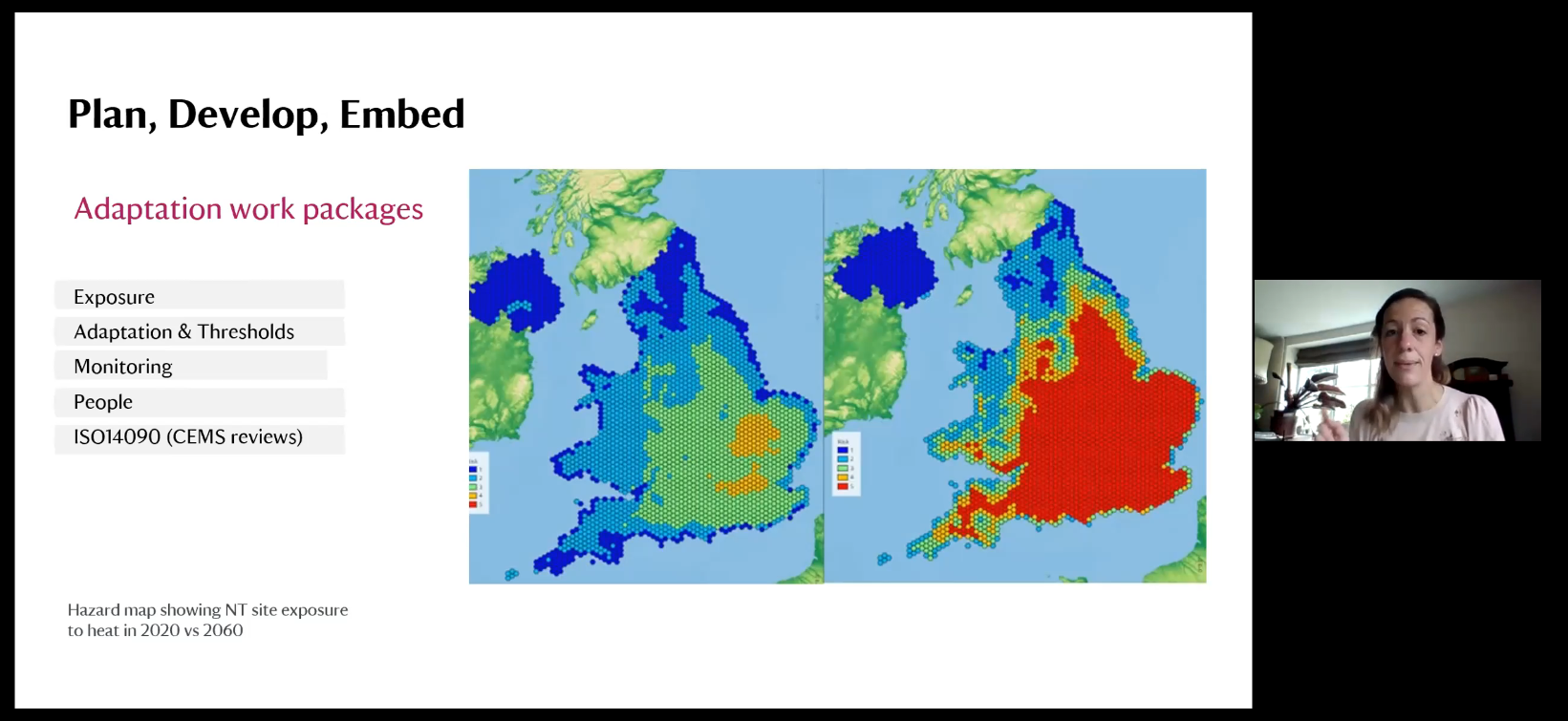

National Trust's Hazard Map

Imogen Sambrook, National Heritage & Climate Consultant at National Trust, spoke about the organisation’s work to understand adaptation and mitigation approaches to conservation and the methodology for assessing the impacts of climate change on heritage.

The National Trust owns over 780 miles of coastland, often affected by climate change, as well as 3,620 listed buildings.

- What does the National Trust need to be aware of?

- What are the hazards it faces?

- What is the likelihood that they will have an impact?

- What do we then need to do to adapt?

- What are the different paths?

What is a climate hazard?

What is being affected – people, visitors, tangible heritage, place, significance? How do you adapt? Do you resist, accept or implement direct change? Why have hazard maps?

There are 6 main hazards that the National Trust is looking at:

- Coastal processes

- Flooding

- Heat/humidity

- Storm damage

- Landslip

- Shrink/swell

Hazard maps can help us understand the risk, help us priorities and develop long term plans. At Plas Newydd, a coastal property in North-West Wales, for example, we can begin to understand how climate change will impact the humidity levels in the building. How will it impact visitors and historic assets.

Panel Discussion

After the keynotes, there was a panel discussion and Q&A chaired by Dr Elyze Storms-Smeets with various stakeholders from the Netherlands and United Kingdom: Eelco Schurer, estate manager of privately owned estate ‘t Medler (Gelderland); Justin Scully, National Trust, General Manager of Fountains Abbey (Yorkshire); Astrid Stokman, water board Rijn & IJssel (Gelderland); Rob Woodside, Historic Environment Forum COP26 Task Group Chair and Estates Director at English Heritage.

Heritage Responds

The Historic Environment Forum COP26 Task Group focused on shedding light on heritage & climate change at COP26. Many people seem to think that old buildings actually contribute to climate change through inefficient heating systems or lack of insulation. The group showed that heritage can be a proactive part of the solution and that there is a need to collaborate, stay committed and keep exploring pathways such as nature-based solutions, energy efficiency, hazard mapping, engagement with local communities and owners.

Find out more about Heritage RespondsFlooding and droughts

Eelco Schurer said that climate change is being experienced in two ways, that is, through droughts as well as flooding. On private estates, both have to be managed at the same time. 500 years ago, the Medler Estate was a very wet area. Back then, they had made little ditches in the ground to get rid of excess water. Nowadays, these ditches are used to let water in. This is a good example of how heritage can contribute to climate change adaptation.

Astrid Stokman said that flooding has always had the attention of the waterboard whereas drought has been a newer issue to deal with. While the Dutch water management system might be world famous, canals were dug too deep and too straight during the second half of the 20th century, focusing perhaps too much on getting rid of water. As a consequence, some of the systems are not able to retain water anymore. Local factors such as height differences and geology are now being used to make the systems retain water better. ‘Going back to the 19th century’ is romantic and unrealistic. We should all strive to get inspired by the past rather than try to recreate it.

Climate adaptation in a water garden

Justin Scully said Fountains Abbey and Studley Royal Water Garden is a heavily engineered 18th landscape with ruins. Its UNESCO designation as World Heritage Site helps to get more attention around the topic of climate change adaptation. High visitor numbers are also useful in showing that climate change has a high impact on local sites in the UK, not just on the Great Barrier Reef for example. In the context of the Skell Valley Project, research is also being conducted in archival records in order to learn from the past. Oral history is another method that is contributing to this building of knowledge about heritage as a solution for climate change.

More about the Skell Valley ProjectConclusions

Climate change is one of the most pressing threats to historic country houses at the moment. The impact is very visible and very real. However, owners are taking more and more measures to make their estates climate-proof.

Data can help get political figures, local communities and stakeholders ‘moving’ and ‘motivated’. However there is another, more problematic issue at hand: How much effort and resources should you put into adapting to climate change? Where do you draw the limit in terms of spending?

Elyze Storms-Smeets warmly thanked the speakers, the panellists, participants and all our Innocastle partners: National Institute of Heritage in Romania (lead partner), University College Ghent in Belgium, Province of Gelderland in the Netherlands, Regional Government of Extremadura in Spain and the National Trust in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (knowledge partner, through INTO).

The project is financed by Interreg Europe, with a total budget of €1,120,335.00 (85% ERDF, 15% co-financing).

More news from Innocastle