Cultural heritage in a changing climate

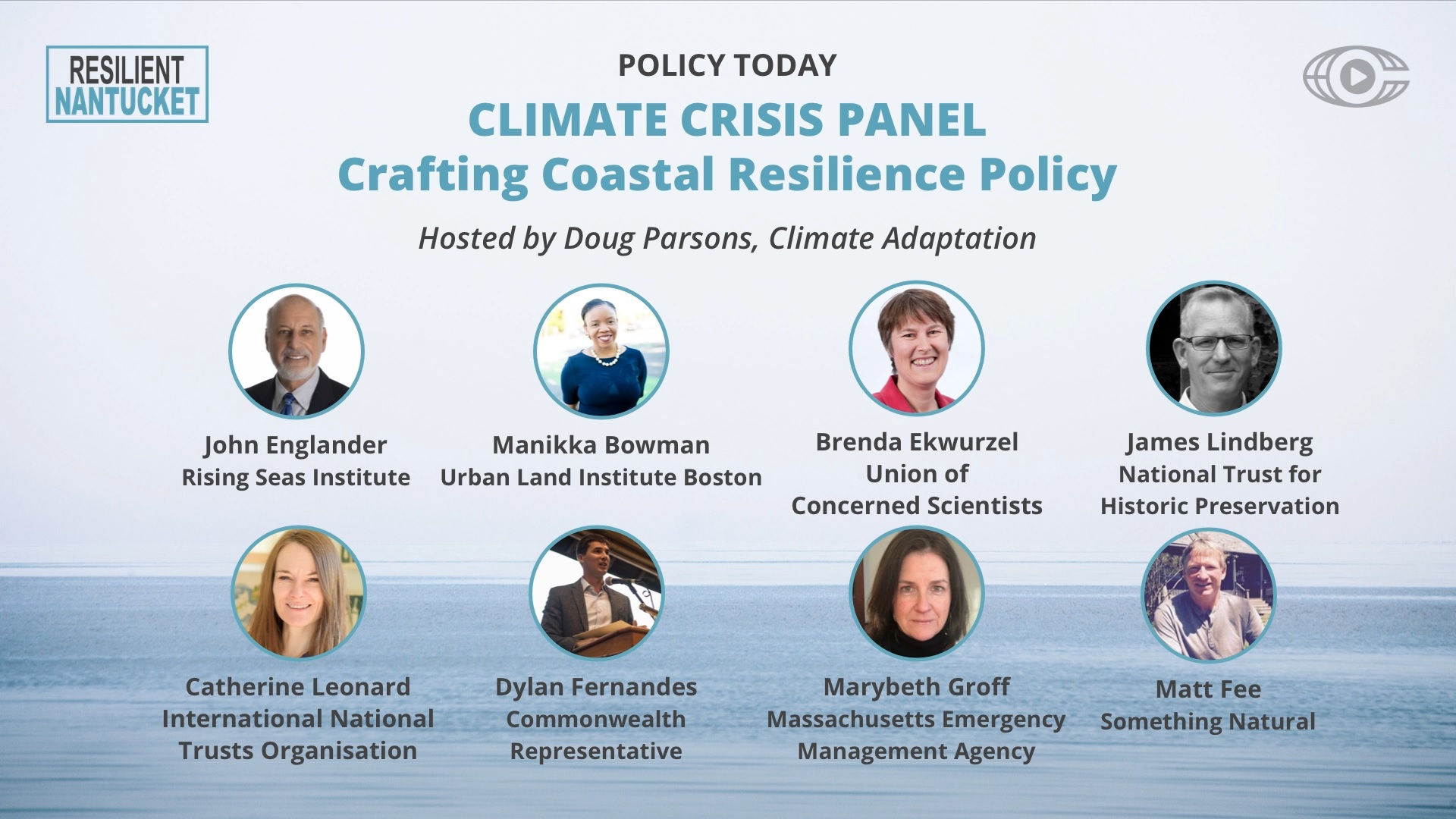

From a climate focussed speech given by Catherine Leonard, INTO Secretary-General, on 23 April 2021 to the Resilient Nantucket Forum

INTO has been involved in the climate change debate from its very foundation. It’s a global issue and needs a global response.

At that time however, some people found it surprising that organisations better known for their cultural heritage portfolios were getting involved in what might have been considered a more ‘environmental’ debate.

But the National Trust model is a holistic one. We look after sites of natural and cultural heritage – tangible and intangible. We run farms and nature reserves, we look after vast acreages of landscape and coast, as well as historic sites and built heritage. That’s not to say that the impacts of climate change on our cultural heritage are any less important, as we’ll see.

I’m not a scientist. But I don’t actually think understanding and responding to climate change is a job just for scientists. We need social science skills. It’s about communication, about inspiring people to take action, about creating alliances and communities of people who share values and care about the same things. And that’s what we in the heritage industry are all really good at.

Extreme weather in Fiji

At the end of last year, Tropical Cyclone Yasa completely destroyed historic buildings in the World Heritage town of Levuka on the Fijian island of Ovalau. Including the Bond Store, a property of the National Trust of Fiji. And the building, already weakened by Cyclone Winston, is now probably lost forever.

We’ve been helping the National Trust of Fiji raise the funds needed to stabilise the neighbouring, iconic Morris Hedstrom building which is integral to the World Heritage Site landscape. But perhaps more importantly serves as a museum, library and community centre, providing an essential resource to local people.

With hurricanes on the increase in the North Atlantic too, many National Trusts, particularly smaller islands in the Caribbean are pioneering new techniques to lessen the impacts of significant storms on the coastline by, for example planting mangrove stands in concrete blocks in the British Virgin Islands or extending groynes and breakwaters in Saint Lucia.

So, climate change is certainly affecting how we look after our places. Stronger storms are one thing. We’re also having to contend with flooding and increased rainfall.

Increased rainfall

Climate change means that Scotland is getting wetter and wetter, with winter rainfall doubling in some areas since the 1960s. The Hill House, designed by famed Scottish architect, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, was built over a hundred years ago when environmental conditions were much drier. And Mackintosh’s innovative use of, at the time, modern materials like Portland cement, have proven less durable than traditional ones.

So, the National Trust for Scotland has placed the Hill House in a large metal box. Pretty radical and not cheap! The walls are made of a metal chainmail like mesh that stops about 90% of rain entering, but allows the building to breathe, and for visitors to still see out from the house, and in from new angles.

Sharing learning about flood management

Flooding is another significant impact. And in Uganda, we have been running a project which exemplifies the need for a coordinated, global response to the threat posed by climate change.

INTO partnered with the Cross-Cultural Foundation of Uganda and the National Trust of England, Wales and Northern Ireland to support communities at the front line of heritage loss due to climate change. Working at two locations with different communities: one in the World Heritage listed Rwenzori mountains where melting glaciers are resulting in the loss of important cultural practices; and one on the banks of the River Nile where we’ve helped build a barrier to prevent the flooding of a cultural site that’s very significant for the Alur and Acholi peoples.

Melting Snow and Rivers in Flood, a project funded by the British Council’s Cultural Protection Fund, is on-going but we’re pleased to have been able to help prevent the loss of heritage, both tangible and intangible, and support climate resilience, through multiple means, from community engagement to sharing learning about natural flood management.

An important part of the project is recording cultural heritage before it’s lost forever. And this is something we’ve seen National Trusts doing increasingly, particularly in Small Island Developing States where heritage inventories or listings can be a bit patchy.

Recording endangered heritage

We’re supporting the Saint Helena National Trust in it’s development of a new Historic Environment Record for this small island in the South Atlantic, using technology which we hope can be replicated on other under-resourced islands. This means that when an extreme weather event hits in the future, response teams will be better able to identify important heritage sites.

National Trusts are also working hard to mitigate against climate change by reducing their own emissions. The National Trust here has pledged to reach carbon net zero by 2030. And other INTO members are making similar commitments.

Introducing new technology

FAI, the Italian National Trust is introducing new technologies at its historic sites and sharing that story with visitors. Talking to them about saving energy and reducing water use.

At Villa Necchi in the centre of Milan, FAI has introduced a geothermal heat pump to air-condition some of the rooms and non-potable water is used to irrigate the garden and for the fountains and toilets. While at Villa Fogazzaro Roi in the Como province, a heat pump system uses water from Lake Lugano to heat the premises.

And the National Trust has installed over a hundred renewable energy projects at its properties in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

So INTO members are using their sites to educate the public about renewable and sustainable energy. Much of this is modern technology, but some is old tech reimagined or repurposed. The pace and rate of climate change is new to us but there is still much we can learn from history.

Learning from the past

When Rippon Lea was built in Melbourne in the 1860s, it’s owner Frederick Thomas Sargood devised a sophisticated water management scheme for the house and garden. An underground water collection, irrigation and drainage system, with water pumped by a windmill, ensured that his precious garden flourished.

In the last few years this rainwater system, which had fallen into disuse, has been repaired by the National Trust of Australia, making the property virtually self-sustainable again, along with solar photovoltaic panels on the roof to meet the annual electricity needs of the house.

The role of gardens

Gardens are interesting bellwethers but also great places to talk to people about climate change. National Trusts across the world are having to rethink their gardens. At Rippon Lea in Australia but also at Ham House in London, where the rapid increase in heat and humidity means that temperatures of over 40 degrees (100 Fahrenheit, which are fairly rare in the UK!) could become commonplace. The head gardener is applying a ‘climate change perspective to every single action in the garden’. In practice this means altering the types of plants grown to those more resilient to high temperatures. And more Mediterranean crops in the vegetable patch, like aubergines and chillies!

Raising awareness

In 2016, I wrote a report for INTO called the State of Global Heritage. It highlighted five major threats to our built and natural environment. Climate change was on the list but not at the top.

In fact, our members told us that public awareness, or lack of it, was the single greatest threat to heritage. And in a way, that actually brings together many of the other threats. Such as poor planning, insufficient funding and, of course, climate change.

Because unless we care as individuals, unless we act and work as organisations towards significantly changing public and official attitudes, we risk letting a large proportion of our built and natural heritage just disappear, through neglect and apathy.

But we can make a difference. By working together, sharing experiences and ideas in forums like this, and continuing to tell the story of climate change in simple, personal ways to the millions of people who love our heritage sites.

You can watch Catherine’s full presentation at the Resilient Nantucket Forum below.

Along with the Climate Crisis Panel hosted by Doug Parsons from America Adapts, and also featuring Jim Lindberg from the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

INTO members featured

Isle of Man

Jersey

Zimbabwe

Australia

Fiji

The British Virgin Islands

Saint Lucia

St Helena

Scotland

Uganda

UK

Italy