Building Maintenance with Innocastle

On 5 August 2021, we hosted a webinar on Building Maintenance, led by Alan Gardner, National Senior Buildings Conservation Manager, with the National Trust of England, Wales and Northern Ireland. It was aimed at colleagues working in regional development roles in Romania and was a welcome practical outcome of the Innocastle project, full of ideas and tips. Some of which are shared below.

Alan began by explaining his role as a buildings surveyor, which is somewhere between a structural engineer and architect – working solely on repairing old buildings. He made the analogy between building maintenance and looking after your car!

Why maintain a building?

Our historic environment contains a unique and dynamic record of human activity. It has been shaped by people responding to surroundings they inherit, and embodies the aspiration, skills and investment of successful generations. It is important to look after it well.

Put protection in the place of restoration, to stave off decay by daily care, to prop a perilous wall or mend a leaky roof ... thus only can we protect our ancient buildings, and hand them down instructive and venerable to those that come after us.

What is building maintenance?

Maintenance is the routine work needed to keep the fabric of a building in good condition.

This can be done by looking: Inspecting the building to assess its condition, noting any problems or areas of concern and seeking advice to determine whether it might be necessary to carry out repairs.

Or by doing: Carrying out specific tasks such as cleaning drains and clearing debris from gutters and rainwater pipes.

Every £1 saved by not carrying out preventative maintenance could cost £20 in repairs within five years.

What should we look out for?

Alan explained that most problems in historic buildings come from roof coverings, gutters, down pipes and drains. You also need to look out for the inappropriate use of construction or previous repair materials, damage caused by plants and animals, and general neglect.

He gave an example of a problem with a gutter that would have involved a builder and a ladder at a cost of around £100-150 escalated into a project costing £3,500-4,000 when nothing was done about it.

He gave an example of a problem with a gutter that would have involved a builder and a ladder at a cost of around £100-150 escalated into a project costing £3,500-4,000 when nothing was done about it.

Good conservation of heritage assets is founded on appropriate routine management and maintenance. Such an approach will minimise the need for larger repairs or other interventions and will usually represent the most economical way of sustaining an asset.

What can I do?

Here are six things you can do to maintain your building.

Record all your repair and maintenance activities in your logbook / health and safety file. Include details of all routine inspections and all work carried out by churchwardens, trades people or professionals. Keep drawings and reports from specialists. And keep your records safe.

Annual inspections should be methodical and comprehensive. Use the maintenance checklist as a guide. Use binoculars to help you see the roof, tower or spire. Take photographs and make notes of what you see. Carry out additional winter weather checks if needed.

Identify all the items you have spent money on in the last ten years. (Check your logbook and/or maintenance plan.) Transfer all these items onto a chart of spreadsheet. Use your chart to calculate the average annual cost of repair / maintenance. Try to set aside an appropriate sum each year.

Identify the hazards. Decide who might be harmed and how. Evaluate the risks and decide on the precautions. Record your findings and implement them. Review your assessment annually and update if necessary.

Don’t work alone unless it is unavoidable. Tell someone where or how long you will be. Carry a mobile phone or some other means to summon help. Make sure you have the appropriate safety equipment.

Things to think about include what might case a fire (fuse boxes, heaters), the potential fuel in an historic building, how fire might spread, how people will escape, staff training, signage, fire detection systems and equipment.

When do I need professional help?

We considered two approaches: Either no one does anything and we always get the professionals in. Or, if we have a high level of competence and confidence, we can carry out a risk assessment and undertake the work ourselves, using appropriate equipment that is fit for purpose.

However, if you have any doubts as to whether you can carry out a task safely, DON’T DO IT! Seek further guidance or employ a reputable tradesperson or professional.

Managing maintenance

A step-by-step approach to buildings maintenance:

- Create a checklist to assess the visual evidence externally and internally

- If there are damp problems, consider the possible sources of moisture ingress and eliminate the obvious causes

- Remedy any defects of faults found

- Seek suitable professional advice where required or if there are any matters of concern

- Carry out cosmetic repairs if necessary

- But remember that you may need permission to carry out some repairs – check what rules apply before you start work

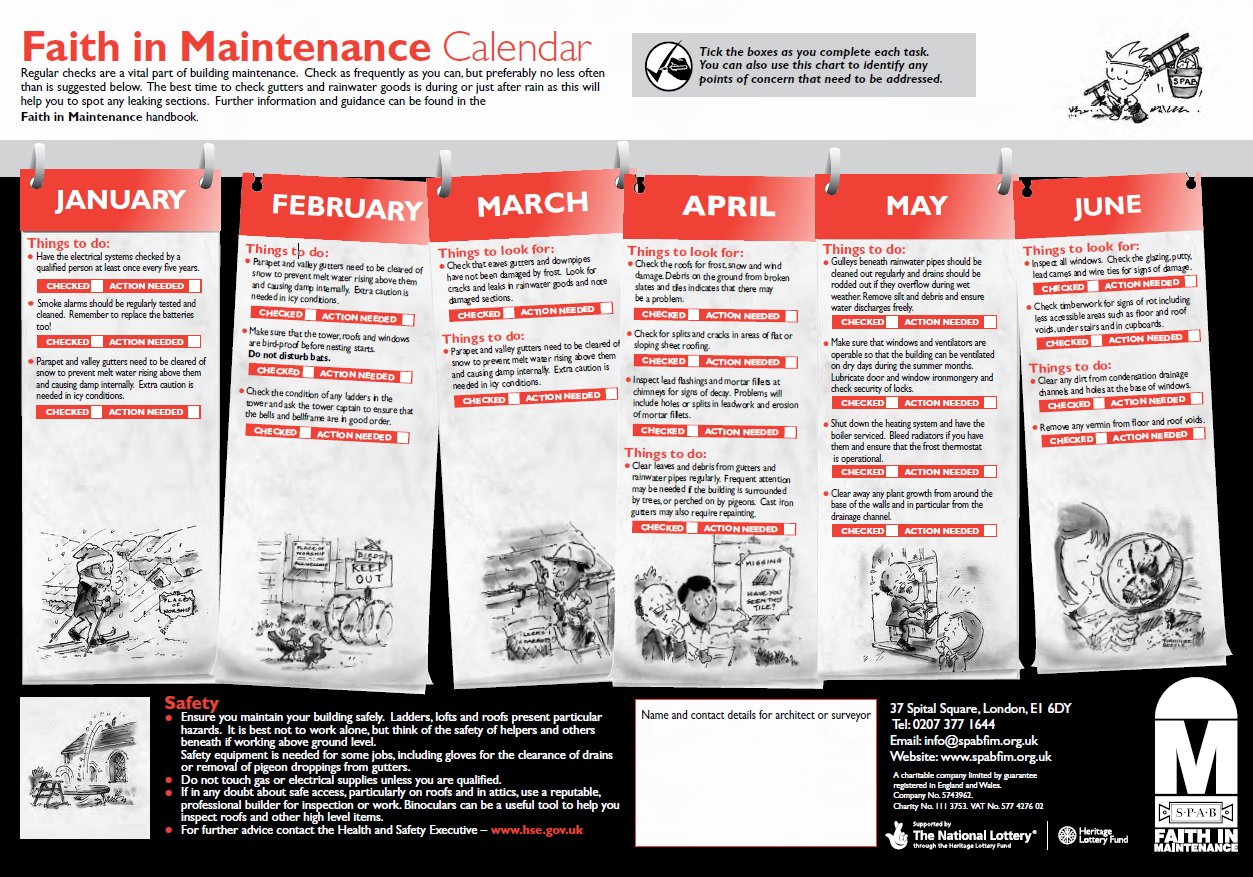

Here is a handy calendar (from SPAB, called ‘Faith in Maintenance’) of the tasks you might want to consider at different times of the year.

All Souls Church, Bolton

We looked at this Heritage Lottery Funded project as a case study. A massive Grade 2* listed church, built by Victorian mill owners, that had stood empty for 30 years. Over that time it suffered from lead theft, arson and lots of problems with the fabric and glazing. When the Churches Conservation Trust surveyed the building, they identified repair costs of around £1m. But no funder would consider such a grant when the church had no use …

All Souls is in part of Bolton where the community really needed an events space, but also meeting rooms and office space. So, the idea was born to turn the church into a local resource.

The project was about so much more than just repairing a building. It was about sustainability, about creating new businesses, engaging local stakeholders and partners, training and outreach programmes. When the work was completed, the building was handed to the community to manage. And the building maintenance plan was a key part of that strategy.

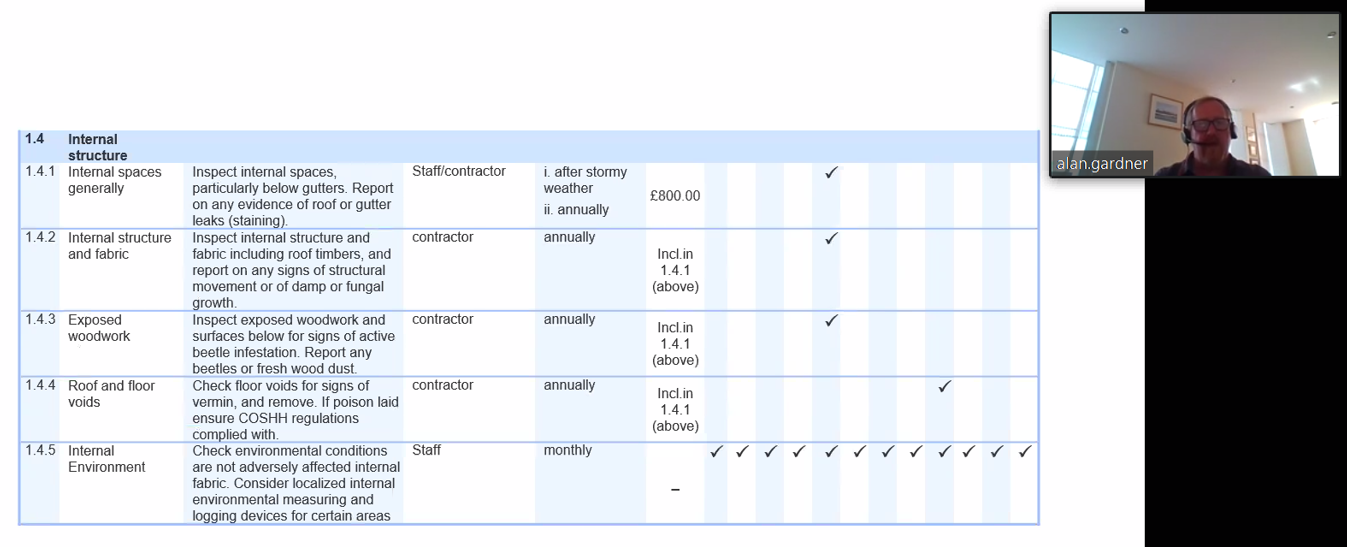

What does a maintenance plan look like?

The maintenance plan is not a conservation management plan in the spirit of the Burra Charter. Neither is it for catastrophic events, like fires.

It identifies cyclical and regular tasks, stipulates who is responsible, when and how often things need to be done and the estimated cost, over a period of several years.

Funders generally want to see a maintenance plan before they will make grants. This protects their capital investment. They also increasingly want to see community engagement and social value as an important part of any funding bid.

Alan said that the Heritage Lottery Fund (now called the National Heritage Lottery Fund) had changed the funding landscape in UK. In the early days it supported some projects and buildings which subsequently failed as business entities. Now business plans, engagement plans, management and maintenance plans are an essential condition of funding applications. Funders are almost less interested in the historic fabric repair, but rather what these buildings can communicate to the wider world and how public money can enable them to survive, be used and enjoyed.

Thank you to Alan for running this excellent workshop and to all our Innocastle partners: National Institute of Heritage in Romania (lead partner), University College Ghent in Belgium, Province of Gelderland in the Netherlands, Regional Government of Extremadura in Spain and the National Trust in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (knowledge partner, through INTO).

The project is financed by Interreg Europe, with a total budget of €1,120,335.00 (85% ERDF, 15% co-financing).

More news from Innocastle